BY STURE JOHANNESSON

Written over 50 years ago, “Psychedelic Manifesto” by Swedish graphic artist Sture Johannesson (1935-2018) remains an illuminating and essential read for twenty-first century researchers of psychedelic art. Provocative, refreshingly humorous and completely devoid of self-censoring, the piece is a valuable key to understanding Swedish psychedelia of the 1960s in general, and Johannesson’s art in particular.

Editor’s Introduction

Johannesson’s art was clearly influenced by his use of psychedelic drugs. This is especially evident in the posters and artworks that he produced in the mid to late 1960s, which contain direct references to psychedelics and the psychedelic experience. Since the artist frequently included the marijuana leaf in his posters, many people associate him with cannabis smoking, which to this day remains a controversial activity in Sweden owing to the country’s “zero tolerance” policy. However, psychedelics such as mescaline and LSD were also vastly important creative tools for Johannesson. Due to being outspoken about his interest in these drugs, the artist was often negatively portrayed in the Swedish tabloid and mainstream media. While it came to have negative consequences for his career, at least financially, it should be said that Johannesson willingly played the role of a scandalous artist acting in opposition to the establishment. In fact, he gladly fed the media with provocative quotes about drugs that, naturally, were seen as highly controversial at the time.

When interviewed by Swedish adult magazine FIB Aktuellt in 1967, Johannesson enthusiastically spoke about his use of psychedelics and cannabis. For instance, as he discusses an elaborate marker drawing with the reporters, Johannesson admits he created it under the influence of hashish, LSD and mescaline. “That’s why it’s so great,” he says of the drawing.[1] Appropriately enough, the interview took place at “Galleri Cannabis,” an art gallery and studio space in Malmö, Sweden, which Johannesson ran with his wife Charlotte Johannesson, also an artist.

Besides talking about – or perhaps one should say promoting – psychedelics in interviews, Johannesson also wrote a “manifesto” dedicated to the psychedelic experience. Written in his native language Swedish under the title “Psykedeliskt manifest,” the piece was originally published in issue 1/1967 of Swedish arts journal Ord & Bild (lit. “word & image”). This “teenage issue,” as it was called on the cover, centred around drugs and youth culture. Ironically, though, Johannesson himself was over 30 years old when the journal published his manifesto.

Today’s online publication of Johannesson’s seminal piece coincides with the 10th anniversary of the Oak Tree Review website, which went live on May 9, 2009. Since the psychedelic poster art of Johannesson has been a recurring theme in several of my articles here on the website, as well as in other media outlets, posting his manifesto on this day seemed a fitting way to celebrate a decade’s worth of writing, editing and publishing pieces on the topic of psychedelia.

– Henrik Dahl

The cultural worker’s most important task in the future is to spread information about these matters. Psychedelic drugs mean freedom, equality and brotherhood. – Sture Johannesson, 1967

*

PSYCHEDELIC MANIFESTO

‘One can demand that a cultural product fulfils one or more of these criteria: that it intensifies sensory experience, creates knowledge of mankind’s situation, eases human relations and inherits a certain general validity.’

(Nordal Åkerman/Olle Svenning: A Socialist View on Culture)

Today, four cultural products exist that have these four characteristics; the psychedelic drugs LSD, mescaline, psilocybin and hashish. The cultural worker’s most important task in the future is to spread information about these matters. Psychedelic drugs mean freedom, equality and brotherhood.

‘Joy of life! He saw it clearly. One should sell joy of life, not kitchen hardware or brown envelopes. Joy of life demanded love as its partner, and this marriage gave birth to ethics, the good and the right acts.’

(Sven Fagerberg: The Costume Ball)

Freedom is not an imperishable phraseological wash-wear costume one puts on in elementary school, freedom is a lump of hashish in tinfoil, the freedom you cannot hide in your boots or underwear without the police finding it, freedom is a ball of tinfoil one squeezes in one’s hand and is ready to throw away when power intervenes, the abused knowledge in society, knowing that power owns truth and that truth is something a group of people can agree upon through democratic working methods and majority principles. The cultural worker must be an artist with no claim to be taken seriously, reliability comes in the form of a cop’s badge. One should sell hashish, not oil paintings or theatre tickets.

‘Communication is everything that brings people together. The communicative field is the in-between space. The in-between space between people. With this we can bid the beholder farewell.’

(Jens-Jørgen Thorsen, Paletten 3/66)

So, truth is something upon which a group of people can agree. But truth’s field lies between legislatures. In the interstice. With this we can bid the prophets farewell. Artists who appear in the galleries as conformist and disciplined members of a parliament for aesthetic theories and ideologies, not dead, but self-amputated. A struggle about gimmicks, rivalry about reviews of critics in watchmen’s uniforms, intellectual hair-splitting and a folksy roll in the hay. Culture distribution? Society’s interest is to administer art and culture, to portion out what is considered safe or useless.

The manifestation of consciousness is a kind of creation, all such things are truth that has the same value no matter how it is articulated, academically or colloquially. A human being with psychedelic experience recognises his or her karma, an original universal truth and human authenticity, in art, poetry, music, theatre and literature, in situations between person and person, between person and thing, between person and divinity. ‘Everything is holy’. (Allen Ginsberg)

Escapism? Not to accept that inner reality is just as real as the outer is a serious mistake made by people who have never tried or have failed to achieve this. Don’t talk about it – take it! Imagination is just a deeper reality. Drug addiction? William Burroughs refers to the Naked Lunch – a frozen moment when everybody sees what is sitting at the fork’s point:

‘Hashish works as a guide to areas in the psyche that one later can return to without taking the drug, that is one can stop smoking hashish when one has become familiar with those landscapes which the drug has opened up the road to – just as it is the case with other psychedelic drugs.’

Alienation? As an artist with an income below the breadline I have been sized up on estimation and penally taxed so that it is impossible for me to work for my living as employed in any company because of sequestered income. This while the military and economic powers that be need not account for or even stick down the service envelope with the big bribes.

‘How many dark hours / I’ve been thinking of this

that Jesus Christ was / betrayed by a kiss

but I can’t think for you / you have to decide

whether Judas Iscariot had / GOD on his side’. (Bob Dylan)

Communication? Wave your hands! Not only sound and light but all matter manifests itself in waves. Communication is waves. We can wave to each other. Wave your hands!

By Sture Johannesson

Posted on May 9, 2019

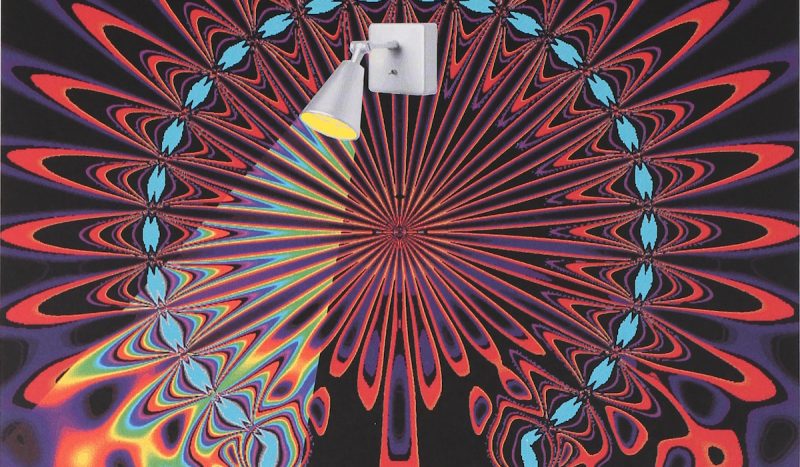

Featured image: A detail of Sture Johannesson’s poster for “Mindblowing!”, an exhibition of mid to late 1960s psychedelic poster art shown at Form/Design Center in Malmö, Sweden in 2011-2012.

Translation: Lars Bang Larsen and Will Bradley.

Note: After its original publication in Ord & Bild in 1967, “Psychedelic Manifesto” has resurfaced in print on a couple of occasions. In 2002, an English translation was included in art historian Lars Bang Larsen and Johannesson’s monograph Sture Johannesson: When the Legend Becomes a Fact, Print the Legend, which is also the translation that is featured on this website. Five years later, in 2007, the manifesto was republished in its original Swedish version in issue 92-93 of art journal Hjärnstorm (Lars Bang Larsen and Maria Hirvi, Eds.).

Notes

1. Lemberg, Arne and Jan Guillou, “Utan en pipa hasch kan jag inte måla!”, FIB aktuellt, No. 3, 1967. The marker drawing that is discussed in the article is titled “Agent Knallrup med rätt att knuffas” (“Agent Browbeat – Licensed to Push and Shove”), and was a collaborative work between Sture Johannesson and Alexander Baldal.